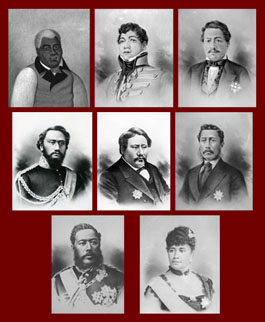

Nā Aliʻi Portraits

There were two traditional paths to power in ancient Hawai‘i, the path of Kū and the path of Lono. Kū, as the god of war, could bring mana to a young warrior through victory in battle while Lono, the god of procreation, could raise up one’s mo‘okūauhau or genealogy through the birth of a child from a well chosen, high ranking mate.

Kamehameha I was successful in both areas. He, as instructed by his kahuna, built the massive Pu‘ukohalā heiau in Kohala, Hawai‘i to honor the god Kūkā‘ilimoku. He carried Kū with him into battle and his victories along this path resulted in his rule of a united Hawai‘i. His lineage however, meant that his descendants’ rule might be challenged. For an answer to this problem he turned to the path of Lono. By deftly taking on one of the highest ranking wahine in the islands, Keōpūolani, as the wahine who would bear his sacred children, he was able to produce the high lineage that would come to form a dynasty.

One traditional method used in asserting the right to rule was the linking of the newly born high- ranking chief to the ancient gods through the recitation of ko‘ihonua (genealogical chants). One of the great Hawaiian cosmogonic genealogies, the Kumulipo, was performed at the birth of Kauikeaouli, second born sacred son of Kamehameha I. This narration linked Kamehameha III to the great gods that were the progenitors of all Hawaiians.

Although genealogy continued as a major factor in determining the right to rule in Hawai‘i, the introduction of foreign ideas of constitutional law and democracy meant that electioneering and politics would also come to be significant components.

After the sudden death in 1873 of King William Charles Lunalilo, who had left no appointed successor, an election was held in which David La‘amea Kalākaua was chosen as Mō‘ī. Kalākaua’s opponent in the election, Emma Na‘ea Kaleleonālani Rooke, was considered by many Kānaka Maoli to have a more significant claim to the throne because of her genealogy. To Hawaiians, the Mō‘ī was a direct link to the divinity of their ancestors, not a mere political position. Emma however, was seen as being pro-British while Kalākaua garnered important support from powerful local American business interests by retreating from earlier opposition to the U.S.-led reciprocity treaty.

This was however, to be the last election in the kingdom as in 1877 Kalākaua appointed his sister Lydia Kamaka‘eha Dominis heir to the throne. Her Majesty Lili‘uokalani became Queen at the death of her brother in 1891. The 1893 Coup d’État against Her Majesty Lili‘uokalani prevented the Queen’s heir apparent and niece, Victoria Ka‘iulani from ever assuming the throne.

*Pukui, Mary Kawena. ‘Olelo no‘eau: Hawaiian Proverbs & Poetical Sayings. Bernice P. Bishop Museum special publication 71. no.308, p38. Honolulu. Bishop Museum Press, 1983.

Location: Bishop Museum ArchivesCollection: Art Collection