Support online education by becoming a member today!

Menu

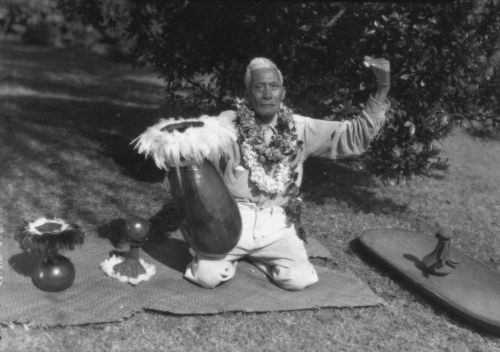

Double gourd drum

Although the terms hula kahiko (ancient) and hula ‘auana (modern), are used to divide styles of traditional dance, these terms are a relatively recent classification of a practice with a very long history. Indeed hula has always carried characteristics specific to place, purpose or performer. The dance has also undergone evolutions throughout its history, often being influenced by the political leaders and situations of the time.

Like all cultural practices, hula was not a static art. New instruments were added to the dance, one of which was the pahu (drum). La‘amaikahiki is credited with bringing the sharkskin drum to Hawai‘i from Tahiti. It is believed that prior to the introduction of the pahu, it was the ipu heke (double-gourd drum) that provided the rhythmic accompaniment to the oli (chant). This was central to the experience as hula is a logo-genic (lyric based) art with the motions of the dancer simply providing assistance in translating the story. It was the ho‘opa‘a, or chanter that beat the ipu heke in order to keep the rhythm.

The hula, like many of the cultural practices of Kānaka Maoli, was misunderstood by the Protestant missionaries that arrived in Hawai‘i. This Native art encapsulated all those aspects of Maoli culture that they abhorred. Hula honored native Akua (Gods), it glorified Maoli history, leaders, and practices, and hula reaffirmed the importance of sexuality and procreation in the maintenance of life. The missionaries deemed hula a paganistic, sexually deviant, and sacrilegious practice. They labeled the dance immoral and worked to ban the practice.

And so it remained for a time. Through much of the 1800s, public exhibitions of hula required a license and were only allowed to be legally performed in Lāhainā and Honolulu, two large seaport towns catering to foreign arrivals. However, several Mō‘ī (sovereign) continued to have hula performed including Kauikeaouli, Kameameha III and Lota Kapuāiwa, Kamehameha IV.

Significantly, King David Kalākaua had three days of hula performed at his grand coronation in 1883. Many in the missionary crowd were appalled and the man who printed the hula program was arrested for indecency. Many Kānaka Maoli however praised the event as an important part of efforts at reviving a part of their culture that detailed their history, language, and customs. While many of the hula in this era relied on the ipu heke and the pahu, new western music also accompanied hula, producing a new style known as the Hula Ku‘i.

Despite all efforts to eliminate hula many of the ancient chants and dances were kept alive within families and passed to descendants. Through the diligent efforts of people such, Mary Kawena Pukui, Patience Bacon, ‘Iolani Luahine, Ma‘iki Aiu and others, some of the most foundational aspects of Hawaiian culture were continued.

Location: Bishop Museum

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

Kuluwaimaka, Hawaiian Chanter. ca. 1930.

Photograph by Ray Jerome Baker.

Collection: Ray Jerome Baker

Call Number: E.C. Hawaiian. Music. Musicians. Chanters.

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

Hula dancers at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel; right: Lily Padeken Wai, member of the Royal Hawaiian Hula Girls; left: Leolani Blasidell. ca. 1950.

Call Number: E.C. Hawaiian. Hula, 1900-, Folder 6.

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

Pen, pencil and wash image by John Webber, ca. 1780.

Collection: Art Collection

Call Number: Art. E.C. Hawaiian. Hula.

Artifact Number: SXC 39933

Accession Number: 1922.129 (189a)

Location: Bishop Museum Archives

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

Left to right: ‘Iolani Luahine, Malia Kau (standing) and Mary Kawena Pukui at Hānaiakamalama (Queen Emma’s Summer Palace)Nu‘uanu, Honolulu, Hawai‘i.

Call Number: People. Bishop Museum Staff. Pukui. [SP 86368]

Accession Number: 1983.245