Support online education by becoming a member today!

Menu

Hawaiian arts, or mea no‘eau, not only served aesthetic purposes but also fulfilled religious, societal and historiographical functions. Mele (music, songs) explain history, carry genealogies, praise individuals, reveal lands, and worship Akua (Gods). As hula is the dance that accompanies Hawaiian mele, the function of hula is therefore an extension of the function of mele in Hawaiian society. While it was the mele that was the essential part of the story, hula served to animate the words, giving physical life to the mo‘olelo (stories).

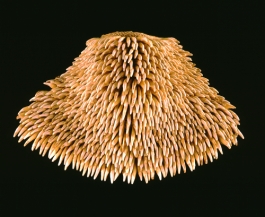

Ancient mo‘olelo are filled with stories of hula, many of them centering on Pele ma (Pele clan including her sister and skilled teacher Hi‘iaka). The practice of hula carried many important protocols and involved a variety of implements. Hālau hula (hula schools) were set up to carry on specific traditions. Dancers learned not only the art of hula, but other skills such as oli (chanting), and the making of various hula implements, like the kūpe‘e niho ‘īlio. This adornment, made from the canine teeth of dogs, consisted of over a thousand of these teeth strung onto olonā cordage. These rattles were usually worn on the calves of male dancers, creating a stunning sound that accompanied the movements of the dancer. Like the ‘ulī‘ulī (gourd rattle), the kāla‘au (stick instrument), and the ‘ili‘ili (small stones), the kūpe‘e niho ‘īlio kept the rhythm of the mele. The hula ‘īlio or dog hula sometimes incorporated this instrument. One such dance was He Inoa no Nahi‘ena‘ena written to honor the sacred daughter of Kamehameha and Ke‘ōpūolani.

The kūpe‘e niho ‘īlio is rarely if ever seen in contemporary hula. With the arrival of western settlers in Hawai‘i, the use of dog as a food was discouraged, making the large quantities of incisors needed for the kūpe‘e increasingly less available. As pressure against hula mounted in the mid 19th century other aspects and implements of the dance became less common.

In the 1920s and 1930s the image of Hawai‘i as a tourist playground was marketed and an ensuing boom of the visitor industry brought rise to a demand for the “little brown gal” hula dancer. This idea continued to dominate the Hollywood iconography of Hawai‘i in the 1940s and 50s as hula shows toured the American continent. Later, in the 1970s and 80s, a cultural renaissance that included hula pushed to re-instill a reverence for the dance as a carrier of Hawaiian culture and history. This cultural revival was to intersect with modern politics when Native Hawaiian gathering rights were challenged, hindering the ability of Kānaka Maoli to collect the plants and materials that were central to their dance. Without these adornments, which were often kinolau (body forms) of the gods, the dance lost a foundational part of its traditional purpose and would be relegated to the aforementioned role of entertainment.

* Pukui, Mary Kawena. `Olelo no`eau: Hawaiian Proverbs & Poetical Sayings. Bernice P. Bishop Museum special publication 71. no. 1438, p156. Honolulu. Bishop Museum Press, 1983.

Location: Bishop Museum

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

Man playing the nose flute and hula dancer in front of hale pili (grass house), Hawai‘i. ca. 1890-1905. Hand-colored lantern slide. Photographer: Henry W. Henshaw.

Call Number: E.C. Hawaiian. Music. Instruments.

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

Pair of ‘ulī‘ulī (coconut dance rattles); Hawai‘i. These ‘ulī‘ulī were probablly exhibited by the Hawaiian government at the Paris Exposition Universelle, 1889. Coconut shell, chicken feathers, cotton and silk, leaf stems, wire, trade cordage, thread, ali‘ipoe. ca. 1885.

Photo: ca. 1980 by Seth Joel.

From: Roger Rose, Hawai‘i: The Royal Isles. (Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1980), pg. 16, no. 153.

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

Hula dancers at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel; right: Lily Padeken Wai, member of the Royal Hawaiian Hula Girls; left: Leolani Blasidell. ca. 1950.

Call Number: E.C. Hawaiian. Hula, 1900-, Folder 6.

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

Pen, pencil and wash image by John Webber, ca. 1780.

Collection: Art Collection

Call Number: Art. E.C. Hawaiian. Hula.

Artifact Number: SXC 39933

Accession Number: 1922.129 (189a)

Location: Bishop Museum Archives

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

“Iles Sandwich [Hawai’i]: Femme de L’ile Mowi Dansant.” Engraving.

Artist: Jacques Arago. Engraver: Augrand.

Call Number: Art. Ethnic Culture. Hawaiian. Dance. Hula.

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

Mrs. Mary Kawena Pukui playing the ‘ūkēkē with Mrs. Timothy (Rosalie) Montgomery; Hawai‘i, 1950.

Collection: General Photograph Collection

Call Number: E.C. Hawaiian. Music. Musicians. Instruments.

Location: Bishop Museum Archives

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

‘Ukulele made in the 1930’s by David Mahelona of koa, mother-of-pearl, brass, plastic, metal, wood, and cat gut. Photograph by Seth Joel. From: Roger Rose, Hawai‘i: The Royal Isles (Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1980), pg.17, no. 164.

Call Number: Hawaii: The Royal Isles

Accession Number: 1976.129

Location: Bishop Museum

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

Left to right: ‘Iolani Luahine, Malia Kau (standing) and Mary Kawena Pukui at Hānaiakamalama (Queen Emma’s Summer Palace)Nu‘uanu, Honolulu, Hawai‘i.

Call Number: People. Bishop Museum Staff. Pukui. [SP 86368]

Accession Number: 1983.245