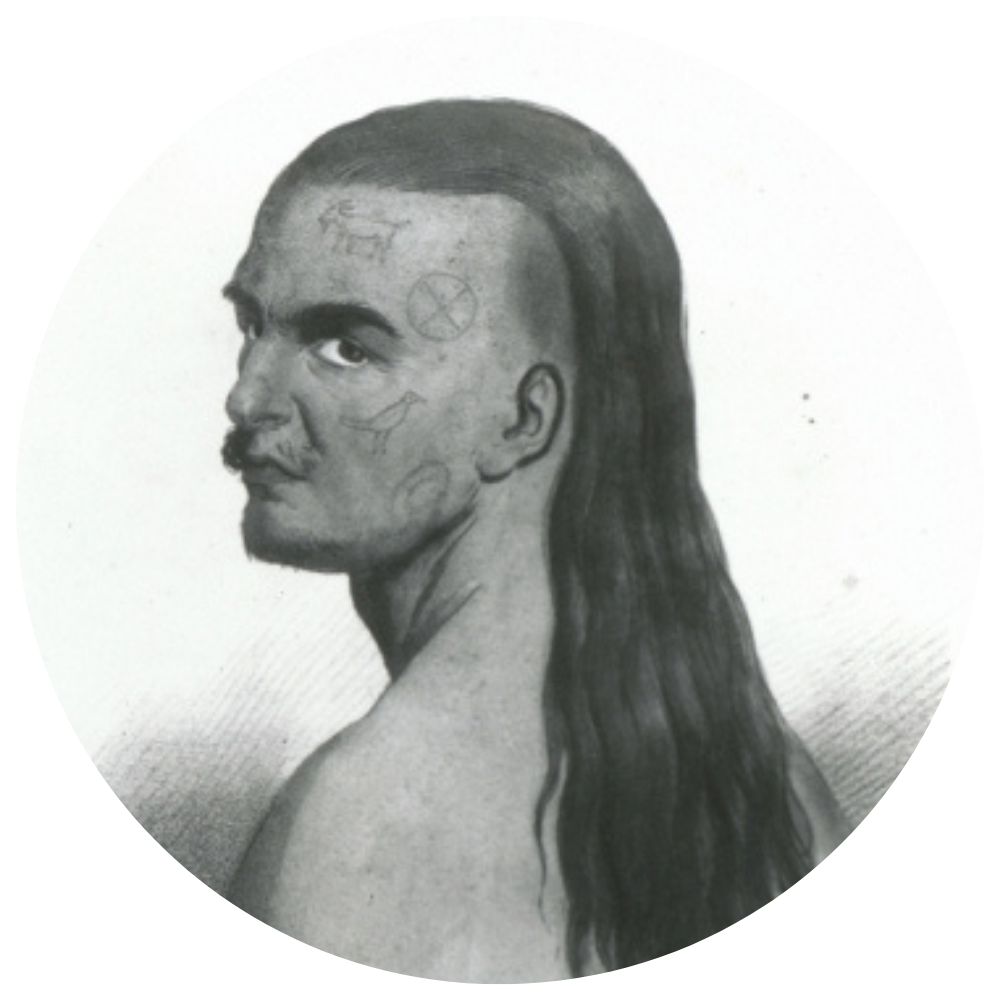

A Man of the Sandwich Islands, Half Face Tattooed

by John Webber (1752-1793)

Tattooing is a Pacific traditional art that has penetrated into the heart of mainstream Euro-American culture. While having been practiced sporadically in other cultures throughout history, tattooing rose to popularity in the west through contact with Pacific peoples. The word tattoo in fact, is an English phoneticization of the Polynesian word tātau or kākau.

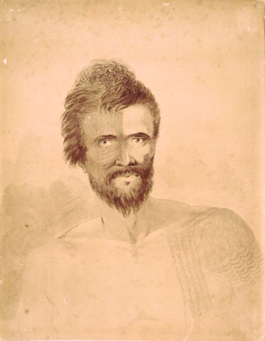

While Captain James Cook and his crew had seen tattooing during their voyages, it was the artist John Webber’s sketches of tattooed Pacific peoples that really brought this important practice to the attention of the bulk of European society.

Much information regarding early Hawaiian tattooing has been lost and Hawaiians also incorporated practices and styles from Sāmoa and other parts of Polynesia. There are however, some well-known mentions of kākau in the oral and written histories. The April 1870 Hawaiian-language newspaper Ke Au Okoa tells of the fearsome Māui warrior and chief Kahekili, who was famous for the head to toe kākau pa‘ele (solid black tatoo) that covered one side of his body. He marked himself in this manner so as to honor an ancestor Kahekilinui‘ahumanu, from whom the revered Mō‘īwahine Ka‘ahumanu received her name. This great Māui ruler and son of Kaka‘alaneo was said to have been a descendant of Kānehekili, the God of Thunder who was black on the right side of his entire body.*

Other classes in Hawaiian society often had their own distinguishing tattoos, as well. Some members of the lowliest class, termed kauwā, were marked by tattoos on the forehead. Male kauwā were used for human sacrifice and were generally avoided not only because of their low rank but also because of talk of their super-natural powers.

Kākau could also mark occupational roles within society. Healers and hula dancers were often tattooed about the wrists and hands. While prior to Cook’s voyages most of the kākau patterns were geometric designs, newly arrived images of foreign animals, objects, and the written word soon began to be incorporated into tattooing motifs. One mo‘olelo speaks of many of the warriors of Kamehameha, in a sign of mourning, tattooing his name and date of death on their bodies.

Tattooing, like many traditional practices, was greatly frowned upon by the Protestant mission. Because of this, it experienced a large decline in usage and number of experienced practitioners. However, a modern day resurgence of interest and pride in what is known of traditional understandings, methods and motifs has begun to return tattooing to a place of significance within Hawaiian society.

* Kamakau, Samuel M. Ke Au Okoa. Buke 5, Helu 51. 7 Apelila 1870

Location: Bishop Museum Archives

Collection: Art Collection

Call Number: Webber