Hale Pili

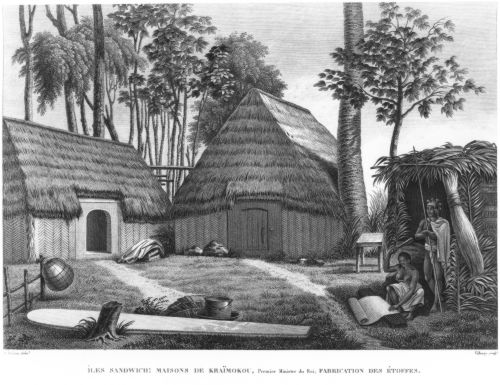

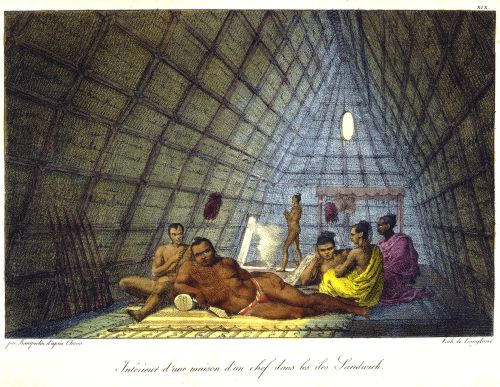

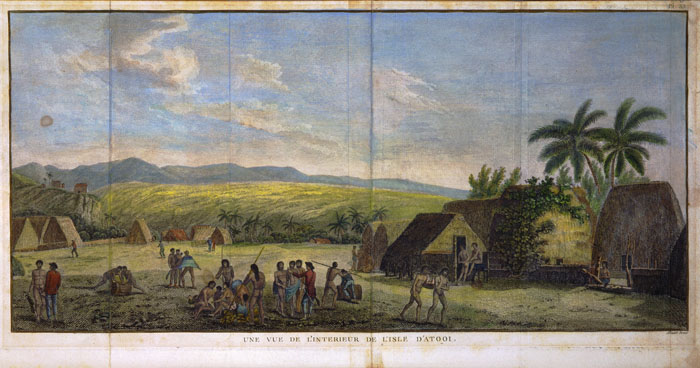

Shelters in traditional Hawaiian society were role specific with explicit designations for each type of structure. The kauhale, or homestead, often consisted of hale noa (house free from kapu) where all slept together, hale mua (men’s meeting house), hale kuke (cooking house), hale pe‘a (menstruation house) and other needed dwellings. The general location of shelters was often determined by the geography of the land. Housing mauka might focus around a lo‘i or hale ku‘a (tapa making structure) while those living makai would often be centered around a hale wa‘a (canoe house).

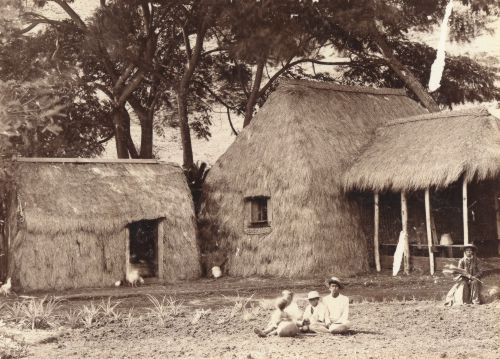

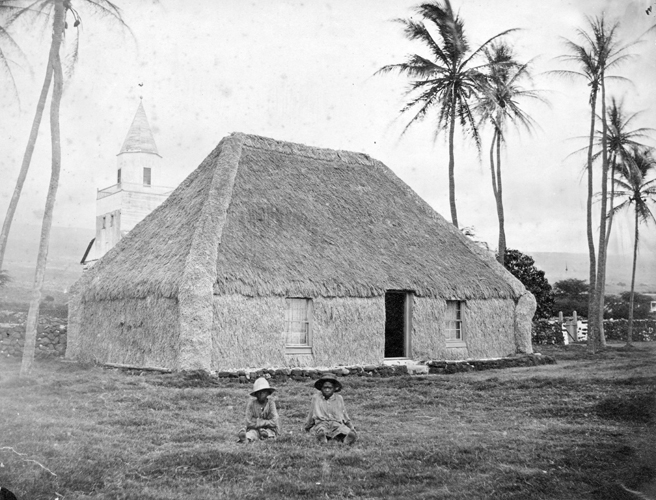

Traditional hale were constructed of native woods lashed together with cordage most often made from olonā. Pili grass was a preferred thatching that added a pleasant odor to a new hale. Lauhala (Pandanus leaves) or ti leaf bundles called pe‘a, were other covering materials used.

There were many loina (rules) associated with the construction of hale. The kahuna ku‘iku‘i pu‘uone, priest who chose the location for a hale, had the final word on the important decision of site selection. The building of a new house was marked with ritual and a feast of dedication. The “birthing” ceremony of a new dwelling centered around the doorway of the house with the cutting of the piko (center, symbolizing the umbilical cord) of the house and offerings of fish. The kahuna o Lono recited a Pule Ho‘ola‘a Hale (House Dedication Prayer).

Hale were built by Kānaka Maoli with millennium old understandings of the land on which they lived. They were familiar with the winds, rains and the other natural elements that would affect the house in the many years to come.

A huge change that came with the end of the kapu system was the mixing of the previously separate places for eating and sleeping. The book Native Planters describes:

The simplicity and orderliness of the hale noa, and with them the sound, normal living of families, were destroyed when the kapu requiring men and women to eat separately was abolished. This meant that food was brought into the living quarters. What had been a clean and neat sanctum for man and wife and their offspring became a free-for-all gathering place for all ages of both sexes. The integrity and meaning of the home no longer existed; with them vanished the orderliness of ‘ohana relationship on which the social and economic functions of the community were built. This was a first symptom of the further deterioration in ‘ohana relationships, including that between ali‘i and maka‘ainana, which was to come about gradually with the later intrusion of foreign and economic and political influences.*

The traditional hale pili currently exhibited at the Bishop Museum was built on site in 1902 from materials that came from an abandon house in Miloli‘i, Kaua‘i. William Brigham, Bishop Museum’s first director, had the posts and rafters purchased and shipped over from Kaua‘i to be reconstructed at the museum where it has now stood for over one hundred years.

* Handy, E.S. Craighill and Elizabeth Green Handy with the collaboration of Mary Kawena Pukui. Native Planters in Old Hawaii: their Life, Lore, and Environment. Bernice P. Bishop Museum bulletin 233. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1991. pp 294-295.

Location: Soon to be reassembled in Hawaiian Hall

Call Number: SP 28933