Support online education by becoming a member today!

Menu

Moena Makaloa

By the time of sustained contact with foreigners in the early nineteenth century, Kānaka Maoli had developed a Native epistemology that included an understanding of the universe and their relation to it based on thousands of years in Polynesia and nearly two millennium on these islands of Hawai‘i. With the arrival of proselytizing missionaries and later foreign ideas of property, government and economics, these lands saw great change. Contrary to much of what has been written, Hawaiians did not sit idly by and watch foreign ideas dominant and proliferate. From the beginnings of continued attacks on Native ways of life, on through the later history of Hawai’i, Kānaka Maoli have spoken out against challenges to their indigenous knowledge. This resistance took many forms and was manifest in many arenas.

Soon after western-style constitutional government began in 1840 to lessen not only the power of the Mō‘ī, but also the inter-dependant relationship between ali‘i nui and maka‘āinana, Kānaka Maoli spoke up in protest. An 1845 petition was published in the Hawaiian-language newspaper Ka Elele titled “Na Palapala Hoopii o Na Makaainana” (Petitions of the makaainana). This active voice of the people concerned continuing the independence of the kingdom that Kamehameha I had established and questioned why foreigners were being placed in positions as officers of the Kingdom government.

Kānaka Maoli also incorporated resistance into traditional forms. In the face of potent moral and legal attacks on ancient traditions like hula, Lota Kapuāiwa, Kamehameha V, helped build resistance to missionary bans on hula by allowing performances to continue and working within the legislature to ease restrictions. Later, King David La‘amea Kalākaua notably called for three days of public hula presentations to be given at his 1883 coronation and again in 1886 at the jubilee celebrating his fiftieth birthday, directly opposing missionary restrictions.

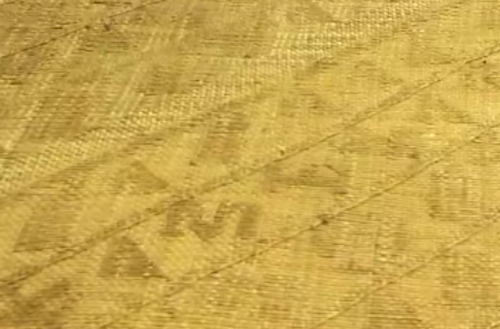

A particularly unique and beautiful form of Kānaka Maoli protest was the makaloa protest mat now held at the Bishop Museum. Makaloa (Cyperus laevigatus) mats woven on the island of Ni‘ihau were exceptionally prized for their softness and the fineness of their plaiting. A May 1874 article in the Hawaiian-language newspaper Ka Nupepa Kuokoa describes a mat that was woven by a woman named Kala’i, “ Niihaus most skillful woman in that particular art”. The mat was plaited in a way as to include lettering in rows throughout the mat. This lettering spelled out a strong protest to the King. This wahine, now 80 years old, voiced her disapproval of the changes she had seen since the time of Kamehameha I. She protested the new difficulties that had come with the move to western-style land tenure and overly burdensome taxes assigned to the people. The protest mat had been intended for King William Charles Lunalilo, but with his untimely death in 1874, the mat was delivered to the new Mō‘ī, His Majesty King David Kalākaua. Bishop Museum curator Roger Rose, in his paper on the protest mat notes, “Although intended for another occasion, the mat with its petition nonetheless proved to be a timely gift, for three days after receiving it King Kalākaua convened the legislature of 1874.”** Significantly, the full text of the woven protest was printed by two Hawaiian-language newspapers Ka Nupepa Kuokoa and Ko Hawaii Ponoi greatly expanding the reach of the resistant voice.

Native voices of resistance would continue on to include voluminous examples surrounding the 1893 overthrow of Queen Lili‘uokalani, the 1993 centennial protests and contemporary calls for Native Hawaiian sovereignty.

*He Moena Pawehe Mahana. Ka Nupepa Kuokoa 2 Mei, 1874.

**Rose, Roger G. Patterns of Protest: A Hawaiian Mat-Weaver’s Response to 19th-Century Taxation and Change. Bishop Museum Occasional Papers, Vol. 30, June 1990.

Location: Bishop MuseumWao Kanaka > Makaloa Protest Mat >

Protest Mat Video

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

Lauhala weavers sponsored by the University of Hawaii extension service; (Lt. to rt.: Mrs. Helen Kekalia, Mrs. Louisa Laumana, Mrs. Daisy Moore, Aunt Alice Kaulili, Mrs. Louise Caster and Mrs. Ellen Smith); Hoolehua, Molokai, 1949.

Call Number: E.C. Hawaiian. Art. Weaving.

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

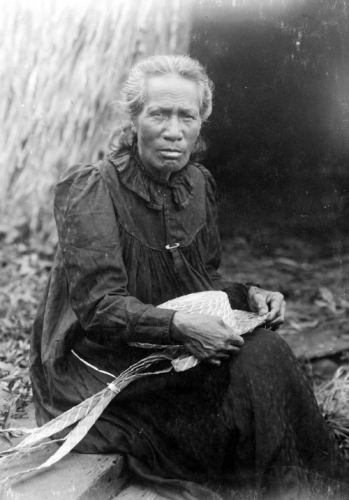

Photo by Ray Jerome Baker, 1900-1915.

Collection: General Photograph Collection

Call Number: E.C. Hawaiian. Art. Weaving. Hats.

Artifact Number: SP 26315

Location: Bishop Museum Archives

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

Makaloa – Umbrella Sedge – Cyperus laevigatus

Photograph by H. Lennstrom

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

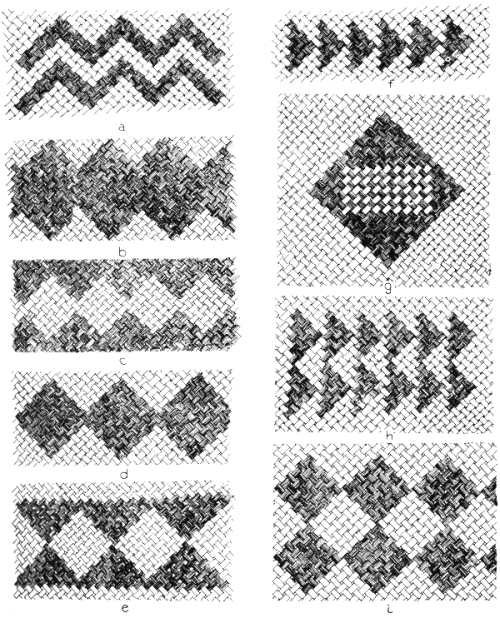

Pawehe makaloa patterns from Arts and Crafts of Hawaii by Te Rangi Hiroa (Sir Peter Buck)