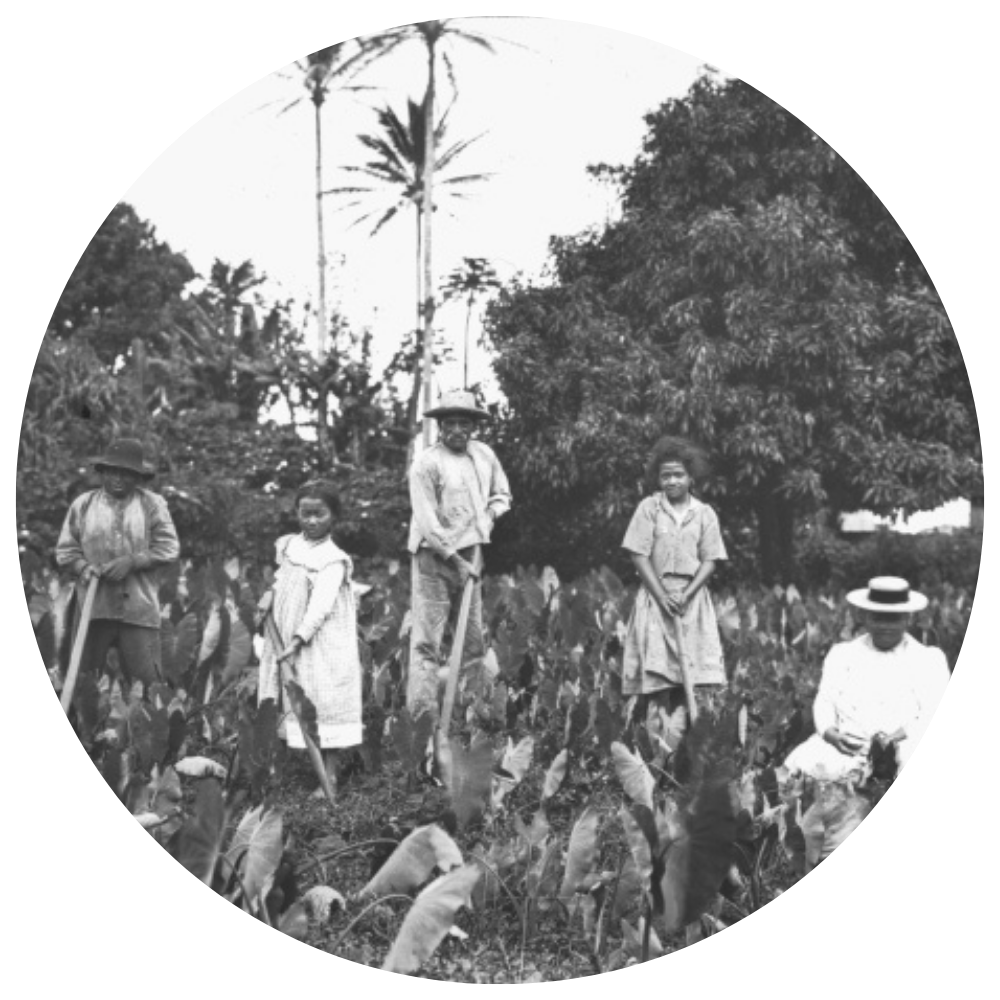

Mary Pukui Pounding Kalo

Ever since the Polynesian navigators that left their homelands to the south arrived in the islands of Hawai‘i, their culture adapted, modified and changed with the new environment and experiences. However, with the arrival of foreign peoples, more dramatic and powerful forces of change came to Hawai‘i. Some of these changes were seen by Kānaka Maoli as detrimental. New views on land tenure, manners of behavior, and a new language, all began to contest basic ways of knowing and relating to the universe that had served Native Hawaiians well for thousands of years.

Kānaka Maoli did not sit idly by when their culture was challenged in a way that they strongly disagreed with. They resisted, continued practices, and worked to preserve their culture. Because of these efforts, Hawaiian culture is not merely a relic of the past to be studied, but is today a dynamic way of life that Kānaka Maoli continue to celebrate and learn from.

Practices such as hula, ‘awa drinking and even surfing survived many attacks throughout the nineteenth century. Resistance and preservation by ali‘i nui and maka‘āinana alike is heavily documented in the Hawaiian-language newspapers. Immediately after the passage of the Organic acts in 1900 that formed the Territory of Hawai‘i, Kānaka Maoli used the system of elected representation to make their voices heard on the issues that were most important to them. The first Territorial legislature of 1901, dominated by the largely Hawaiian, Home Rule party, passed laws promoting the growing of taro, the use of the Hawaiian language, and the honoring of their then-deposed Queen, Lili‘uokalani.

Later, many Kānaka Maoli made dedicated individual efforts to preserve and perpetuate the culture of their kūpuna. One of the most fruitful of these efforts was the work of Mrs. Mary Abigail Kawenaulaokalaniahiiakaikapoliopelekawahineaihonua Pukui. Mrs. Pukui was born in 1895 in Kā‘ū, Hawai‘i to Mary Pa‘ahana Kanaka‘ole and Henry Wiggin. Raised and taught the Hawaiian language, hula and other customs by her grandmother, Mrs. Pukui developed a passionate drive to perpetuate and archive the ways of her kūpuna for future generations. She began translation work at the Bishop Museum in 1928 and worked tirelessly to gather oli (chants), mo‘olelo (stories), hua‘ōlelo (words) and ‘ōlelo no‘eau (proverbial sayings) in order that the future generations of Hawaiians would benefit. She traveled the islands taping hundreds of hours of informal interviews with Hawaiian-language speaking elders. This ‘ike (knowledge) has become an incredibly rich primary source collection that is accessed today by students and the public alike. Mrs. Pukui continued actively writing, recording and preserving materials until her passing in 1985. She authored or contributed to such essential works as the Hawaiian-English Dictionary, ‘Ōlelo No‘eau, Native Planters, Nana i Ke Kumu and many others. Her daughter Aunty Patience Bacon continues the work of her mother at the museum today.

Involvement and perpetuation in other areas of culture continues. The voyaging canoe Hōkūle‘a continues to teach and inspire and today revivals of the ancient rites of the Makahiki festival are celebrated on every island. Hawaiian-language immersion schools, begun a mere two decades ago, have taught thousands of keiki the ways of their ancestors in their kupuna’s native tongue.

Location: Bishop Museum Archives

Collection: Moving Image: Poi, Imu, Lauhala, Tahitian Dancing

Call Number: 1977.0182.0014

Audio

“He Mau Inoa Kalo” performed by Kuluwaimaka