Bishop Museum's Catalog and Accession Book

created between 1898 and 1901

Museums as institutions are devoted to the collection, preservation, study, and display of objects of lasting interest or value. When museums present objects and accompanying text within exhibits, they create a narrative concerning the larger context – era, people, and culture – from which the objects come. Contemporary museum studies programs have offered a determined call for institutions to better reflect Native representations of their collections. By offering Native understandings concerning their own ways and worldview, visitors begin to hear from a people, rather than merely about a people.

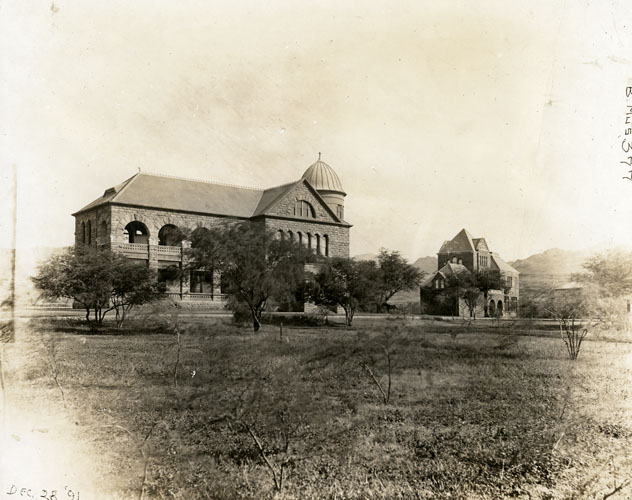

Charles Reed Bishop founded the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum (BPBM) in 1889 in honor of his deceased wife, Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop (1831-1884). Princess Bernice, as a member of the royal family and mo‘opuna kuakahi (great granddaughter) of Kamehameha I, had inherited many treasured objects from this sacred line including the magnificent collection of her cousin, Princess Ruth Ke‘elikōlani (1826-1883). The preservation and display of these objects had been a desire of both of these chiefly women. When a third high ranking chiefess, the former queen, Emma Rooke (1836-1885), passed only a year after Bernice her significant artifacts joined the others, forming the foundational collection of the proposed new museum. Construction of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum began in 1889 in Kalihi-Pālama on the grounds of the campus of the Kamehameha School for Boys. The museum opened to the public in 1892, and later added Polynesian Hall in 1894, and the “Victorian masterpiece” named Hawaiian Hall in 1903.

The display of objects of interest had an earlier history in Hawai‘i. In 1833, Seaman’s chaplain, Rev. John Diel, began displaying artifacts in the basement of the Seaman’s Bethel (church) in Honolulu, attracting the occasional interested visitor. Diel enlarged his collection in 1837, seeking to preserve the objects of what he saw as a dying race. He named his new “museum” The Sandwich Islands Institute. It opened with among other odd curiosities, a large black bear.

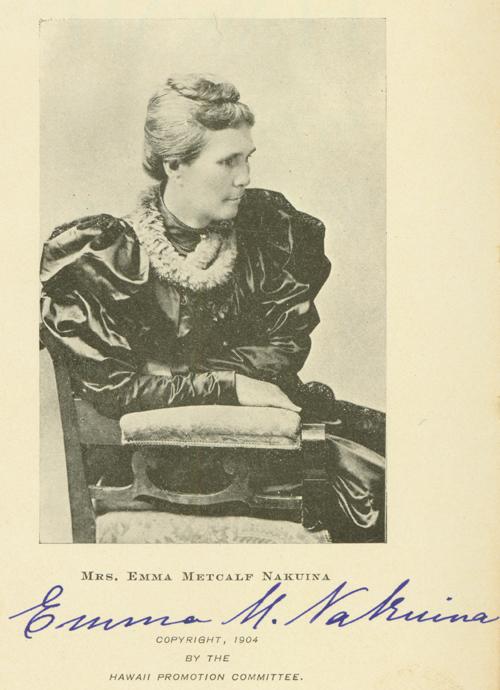

In later decades, the Hawaiian Kingdom government came to recognize the value that a museum might offer as a site of cultural preservation and national voice. On July 29, 1872, King Lot Kapuāiwa (Kamehameha V) signed into law an “Act to establish a National Museum.” The Hawaiian National Museum opened in 1875, during the reign of King David Kalākaua, as a small collection with a meager budget. It was housed in an upper room of Ali‘iolani Hale, the government building. As Kalākaua began to focus his attention on nationalistic projects he would increase the museum’s budget ten-fold and name Emma Nakuina, the museum’s first Native curator, as head of the institution. However, in 1887, the newly imposed “Bayonet Constitution” greatly curtailed the king’s power and slashed funding for the National Museum. Discussions soon began concerning a possible transfer of the government collection to Charles Bishop’s proposed museum. In January of 1891, word arrived by ship of the death of King Kalākaua. BPBM Director William T. Brigham, reportedly anxious over what might become of the national collection, collected and transferred many of the artifacts to the newly founded museum now under his direction. On June 22 of that same year the museum opened to the public with a mission to “preserve and display the cultural and historic relics of the Kamehameha family that Princess Pauahi had acquired.” The nation’s new sovereign, Her Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani, was the first guest.

In 2006, more than a century after its founding, this preeminent museum closed the main hall for a three-year renovation. The project offered an opportunity to re-examine how best to present the cultural and physical treasures of a people and their nation. One focus was to use the collection to better engage the present. A focus of the Hawaiian Hall Committee was to end the practice of viewing the Hawaiian materials as objects of a “dying or lost culture” and instead highlight the connections between past and present that platform a living culture. Contemporary community leaders, Native scholars and educators, practitioners, and elders were consulted in a process that produced what one Native member termed “a state-of-the-art museum that embodies a Native Hawaiian world view, layered in meaning and authentic in voice.” Oli (Hawaiian chants) now fill the hall and Hawaiian-language texts appear in many of the display cases, providing new links to ancient understandings. The works of Native contemporary practitioners are shown beside pieces from their ancestors.

The museum is working to promote interaction between the collection and the public that focuses on current context. An historic 2010 exhibit entitled “E Kū Ana Ka Paia: Unification, Responsibility and the Kū Images” reunited in Hawai‘i the three remaining ki‘i (statue) of the akua Kū for the first time in over 100 years. Education projects such as the curriculum based Hawai‘i ALIVE website and the storytelling of Ola Nā Mo‘olelo (the stories live) seek other ways to link visitors with the outstanding collections. The museum is presenting contemporary audiences with connections to a tremendous living and growing body of knowledge – a knowledge that has been carried forward by a people with one hundred generations of experience in these islands.

Image: Bishop Museum’s Catalog and Accession Book

Compiled by Allen M. Wolcott between 1898 and 1901 under the direction of Bishop Museum’s first Director Dr. William T. Brigham. The Director’s Report for 1901, (Occasional Papers I (5): p.5) states: “Mr. Wolcott has completed the accession book, comparing each specimen with the description and number in the most painstaking manner.”

Call Number: Q_205663