Support online education by becoming a member today!

Menu

Contemporary Issues

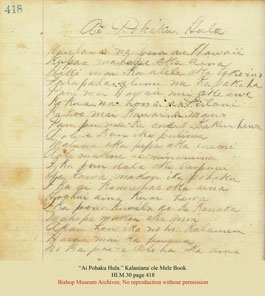

Mele (song, music) has always been a fundamental medium of Hawaiian communication. It has among other things, served to honor beloved leaders, to cherish loved ones, to recall a proud history and to resist things seen as unjust. Perhaps the most famous “song of resistance” in Hawai‘i is a mele titled variously “Kaulana Na Pua” (Famous are the Flowers), “Mele Ai Pohaku” (Stone Eating Song) and “He Lei no ka Poe Aloha Aina” (A Lei for Those who Love the Land). This song was a reaction to the Coup d’État of January 1893. The plan of the newly empowered oligarchy for immediate annexation to America was thwarted by a U.S. Presidential investigation. At this point the Provisional Government began the process of trying to hold onto power as an unpopular, ruling minority. They declared martial law, threatened newspaper editors and took the powerful step of requiring all members of the government, from cabinet ministers to teachers, mail-carriers and policemen, to take an oath of allegiance. If they did not forswear support of their monarch, Queen Lili‘uokalani, they would lose their livelihoods. Even facing the difficulties of surviving without an income, many government employees refused to sign the oaths. Included in this group were members of the Royal Hawaiian Band. Since 1836 the band had represented Ka Lāhui Hawai‘i (The Hawaiian Nation) and at this time of great turmoil these subjects refused to sign any denial of their Queen’s right to rule. After meeting with bandleader, Ellen Kekoahiwaikalani Prendergast, a song of resistance was written. The song spoke proudly of the pua (subjects, children) of Hawai‘i and their steadfast support for their beloved Queen and country. The song was much in demand among the citizenry and would be printed in several Hawaiian-language newspapers. It would come to symbolize a call for justice and recognition of Hawaiian sovereignty.

This steadfast resistance of Kānaka Maoli would be recalled again through song in Jon Osorio and Randy Borden’s tunes “Hawaiian Soul” and “Ea Kaho‘olawe”. These mele honored those, including George Helm and Kimo Mitchell, that had led the way on an issue that seemed to touch the very na‘ao (mind, heart) of what it was to be Hawaiian; the ancient relationship of man and his elder sibling, the land. A group titled the Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana had occupied the island of Kaho‘olawe in order to stop the decades old target-practice bombing of the island by the United States military. Helm and Mitchell sacrificed their lives to this struggle, as both were “lost at sea” in 1977.

Issues of land use came to a head once more in the 1980’s at Mauna Kea, home of the goddess Pele, when the development of geothermal wells called for drilling into the mountain in order to tap steam energy. A group that included Kumu Hula Pualani Kanaka‘ole insisted that to tap into the mountain was to seek to remove the very life-blood of Pele. Oli (chant) and mele (music) were integral parts of the groups honoring of Pele and resisting those who sought to defile her.

Kaulana Nā Pua, as a song of resistance, seemed to come full circle during the 1993 Centennial observance of the overthrow of Queen Lili‘uokalani. Thousands gathered at ‘Iolani Palace and sang this revered mele. One hundred years after the song was penned as a defiant stand against those who sought to separate a people from their Lāhui, Kānaka Maoli again proudly sang their resistance and their call for justice.

Location: Bishop Museum Archives

Collection: Mele Collection

Wao Kanaka > Kaulana Nā Pua >

Jr Coleman voyaging

Wao Kanaka > Kaulana Nā Pua >

Contemporary Land Issues Regarding Mauna Kea

A short video that looks at the issues surrounding Mauna Kea; as a Hawaiian sacred site and scientific research facility. Excerpts from PBS Doc “First Light”

Location: Hawai‘i ALIVE

Image from Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu, Hawaii. Images are not to be re-used without permission.

Protect Kaho`olawe `Ohana approaching the Island of Kaho`olawe by boat, Hawai`i; George Helm holding a coconut to plant, 1977.

Collection: General Photograph Collection

Call Number: Geography. Kaho`olawe. Protect Kaho`olawe `Ohana.

Location: Bishop Museum Archives