Nūpepa ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi

Hawaiian-Language Newspapers

Hawaiian-language newspapers published during the 19th and early 20th centuries in Hawai‘i served as both an important site of current dialogue and a purposeful repository of indigenous cultural and historical knowledge. During much of the Hawaiian Kingdom era, an almost fully literate, informed, and active citizenry populated the nation. Native Hawaiian intellectuals, political and religious leaders, and everyday kānaka (people) filled the pages of nearly one hundred different newspapers with over one hundred and twenty thousand pages of testimony about their lives, their lands, and their lāhui (nation). These contributors to the historical record were often making a distinct and purposeful documentation of their lives and beliefs, and the lives and beliefs of their kūpuna (ancestors), for the benefit of their mo‘opuna (descendants). The collection, preservation, and processing of this incredible resource, matched with a contemporary explosion of demand for primary source materials concerning Hawai‘i’s past, has begun to bring to fruition the plans of these prescient writers of the past.

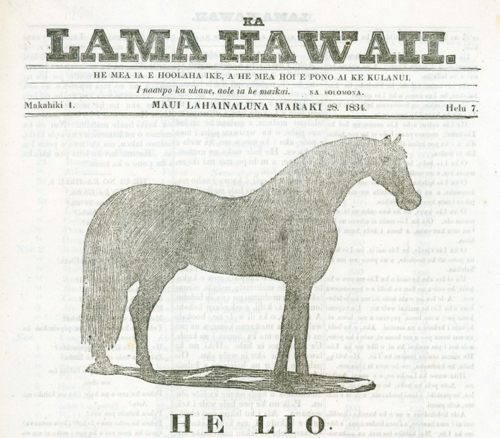

Print technology arrived in Hawai‘i in 1820. The American Protestant mission, well aware of the proselytizing power of the written word, sent a Ramage press aboard ship with the first company of missionaries on their 18,000-mile journey from Boston to “the Sandwich Islands.” The press was installed inside a thatched-roof building on the mission grounds in Honolulu. On January 7, 1822, the Ali‘i Nui (high-chief) and Governor of Māui, Ke‘eaumoku, inked letters to paper for the first time in the islands, creating the initial page of the first spelling book in Hawai‘i. In 1834 the first Hawaiian-language newspaper, Ka Lama Hawaii (The Hawaiian Torch), was printed at the mission-run Lahainaluna School on Māui.

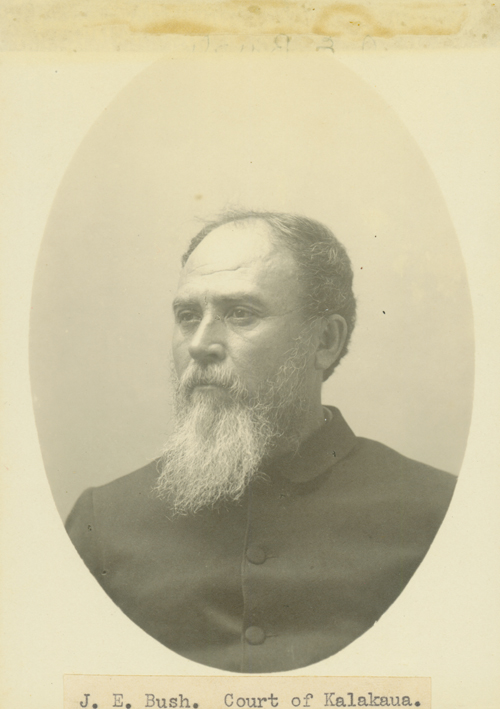

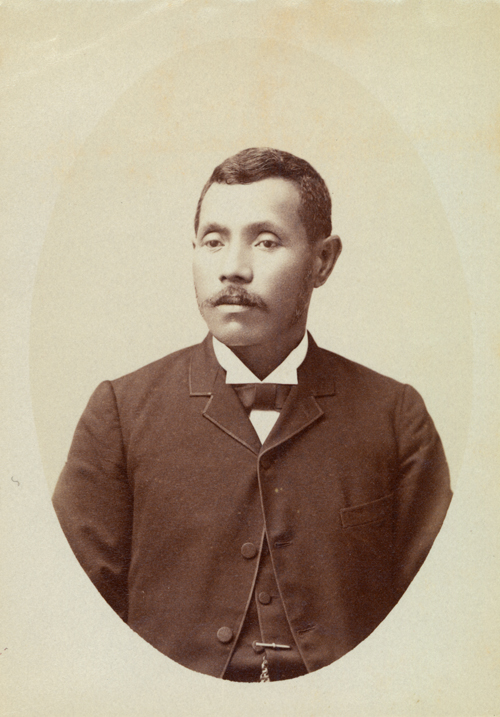

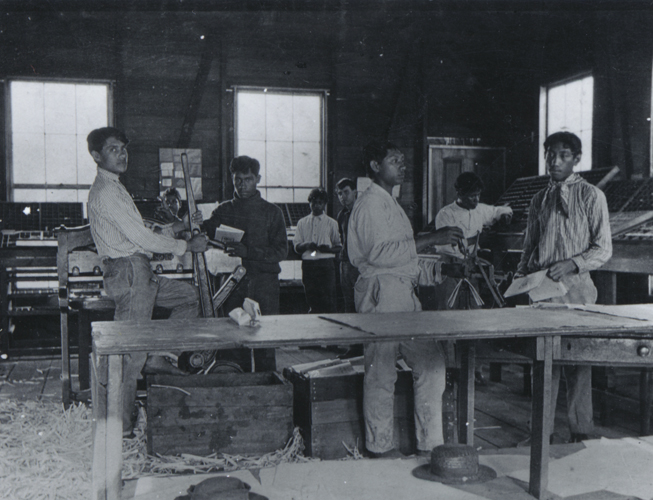

Over the next three decades, a prolific flow of printed materials (over 100 million pages) would flood the Hawaiian Islands with text, the vast majority of which was religious or governmental in orientation. Native Hawaiians quickly learned all aspects of the publication trade and filled the staffs of the early newspapers. While they were indeed significant contributors and producers of this early material, an explosion of Native voice within the papers would come with the creation of Ka Hoku o ka Pakipika (The Star of the Pacific) in 1861. This newspaper, originally owned by Prince David Kalākaua, was the first Native owned and edited newspaper in the Hawaiian Kingdom. Many Native Hawaiian editors followed including Joseph Kawainui, J. K. Kaunamanu, David Keku, Joseph Poepoe, William Pūnohu White, the husband-wife team of Joseph and Emma Nāwahī, and others. This significant shift meant a noticeable change in the character of the material published. Traditional knowledge concerning fishing, navigation, canoe carving and other skills, as well as stories of renowned koa (warriors) and legendary ali‘i (chiefs), began to fill the newspaper pages.

With epidemic disease continuing to take a tremendous toll on the Native population, many contributors to the newspapers were clearly aware of the invaluable link that this medium might serve to future generations. Expert genealogists, cultural specialists, and historians contributed what they knew. More newspapers opened and soon a “Printer’s Row” occupied Merchant street in downtown Honolulu. Inter-island ships carried the papers throughout the Kingdom to a waiting population. The Hawaiian-language newspapers were vibrant, diverse, and even contentious, with differing opinions produced by a variety of editors, both Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian alike. A national dialogue discussed the pertinent matters of the day throughout the isles.

In the period following the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government in January of 1893, many Hawaiian-language newspapers became central sites of contestation against the new Provisional Government. Native editors such as Kahikina Kelekona and Joseph Nāwahī offered voice to those who were devoted to the restoration of their queen and the continued independence of their nation. These editors persisted in their attacks on the government, making strong calls for the restoration of their Queen, in spite of newly enacted “Sedition Laws” that were being used to arrest and harass opposition papers. Ke Aloha Aina, run by Emma Nāwahī after the death of her husband Joseph, printed communications from Her Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani, keeping a tense and worried nation informed and connected to their beloved monarch.

More than a century later, these writings and innumerable others are being made more accessible to researchers, writers, and the general public. The dedicated work of many committed archivists, librarians, teachers, and students is linking people from around the world with the knowledge of Hawai‘i’s past. In 2001, in partnership with the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, Alu Like, and Hale Kuamo‘o, the Ho‘olaupa‘i Hawaiian-Language Newspaper Project launched with the goal of providing online digital access to the Hawaiian-language newspapers. The website (http://www.nupepa.org), hosted within the Hawaiian Electronic Library site Ulukau (http://www.ulukau.org), has since grown to contain nearly fifty titles and 25,000 pages of material.

Image: Ka Lama Hawaii, March 28, 1834.

Location: Bishop Museum Library