Pōhaku kuʻi ʻai Collection

Ke hō‘ole mai nei o Hāloa.

Hāloa denies that.

An open poi bowl meant that no business or ill will was to be discussed lest Hāloa, the taro plant, be offended.*

As the hiapo (first-born child) of the deities Wākea and Ho‘ohōkūkalani, Hāloa-naka, the kalo plant, holds important kuleana (responsibility/privilege) in the relationship between Kānaka Maoli and the land that surrounds them. The second born to these gods, named Hāloa in honor of his elder brother, is ancestor to all Hawaiian people. In Hawaiian knowledge, it is the duty of this younger sibling to honor and serve the elder and in turn the elder sibling will provide for them. This inter-dependant relationship between man and the land serves to connect the fate of both.

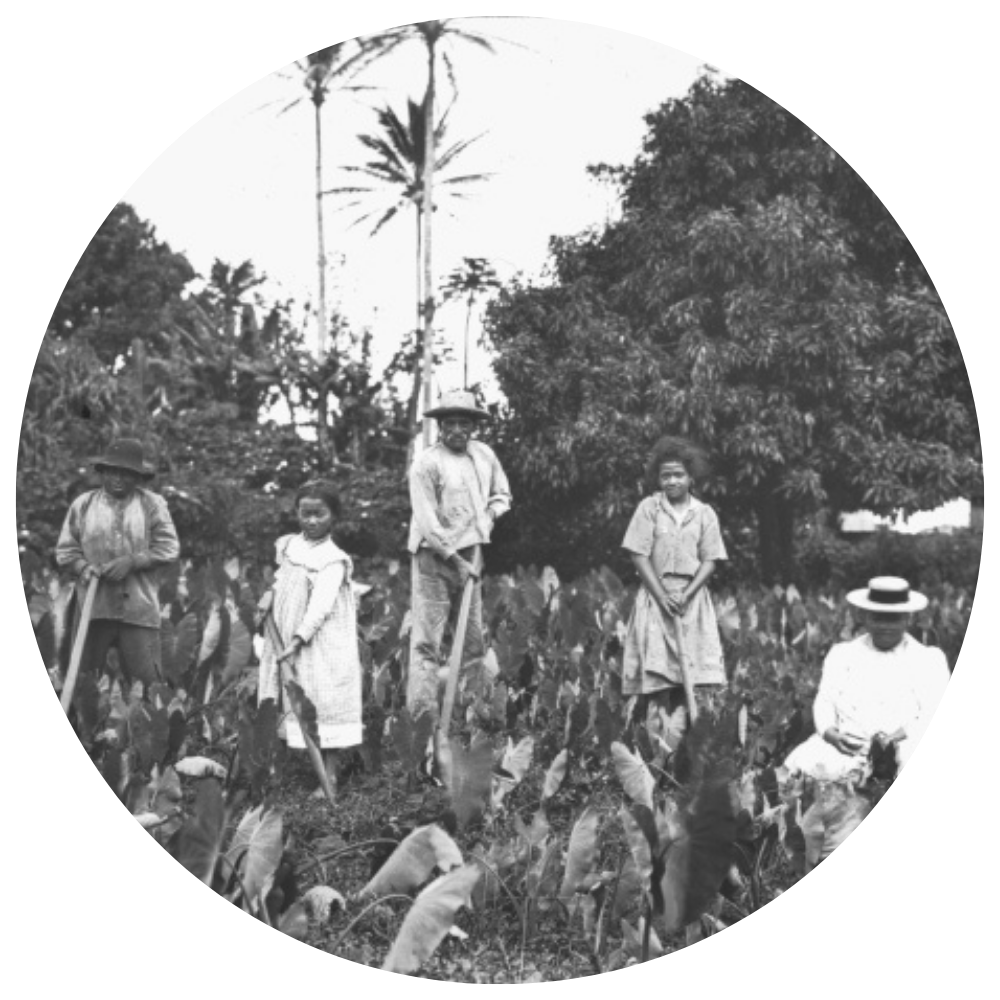

Kalo (Colocasia esculenta), a representation of the land, was consumed by Kānaka Maoli as the primary food in traditional society. The partaking of foods, as kinolau (myriad bodies) of the gods, was one way of getting nearer to the gods. The planting, harvesting and consumption of kalo were all treated with great respect, shown through the many protocol that surrounded these practices.

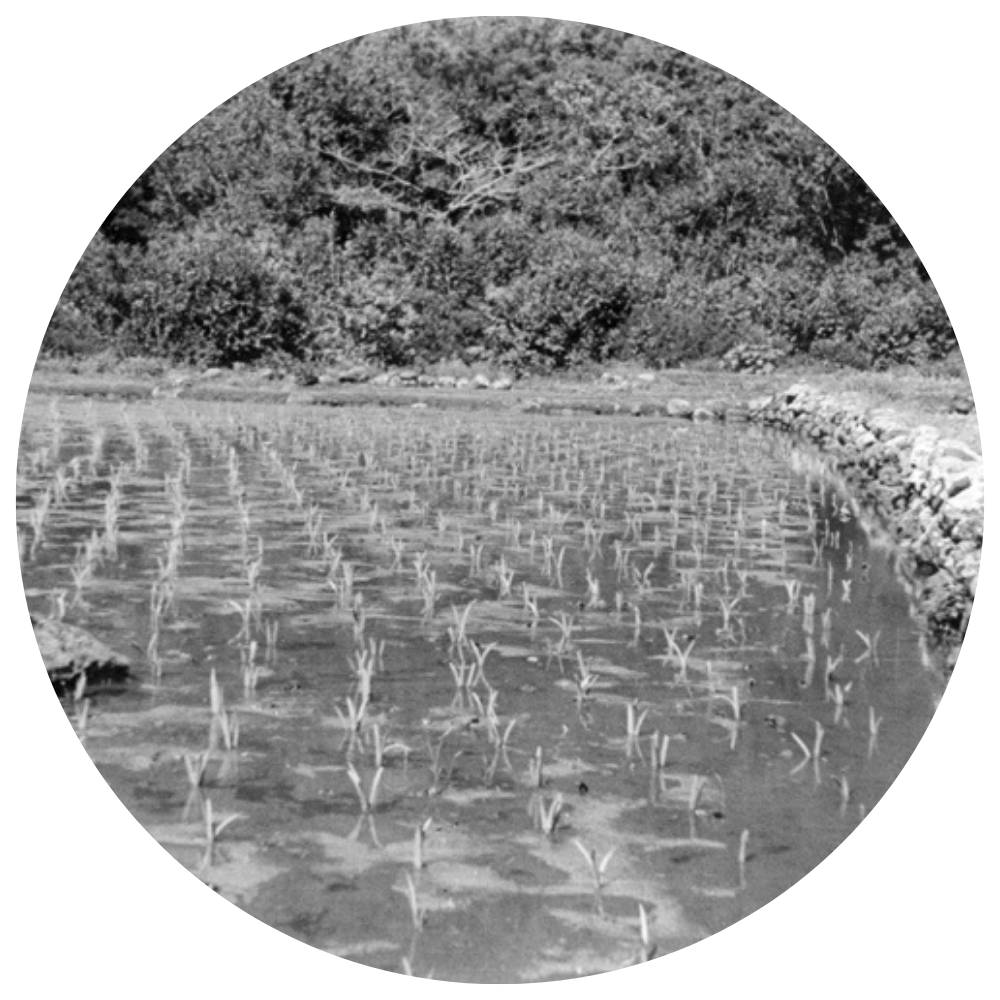

Kalo could be grown in either lo‘i (wetland patches), or in the case of areas with much less rain, mala (dryland gardens). Wetland taro gardens were an integral part of an inter-dependent system that often stretched from mountain to sea. Entire communities worked together to keep kahawai (streams) and ‘auwai (ditches) clean and running so that all farmers within the system could benefit from the clean, cool waters of the main streams. A land that was full with taro patches was considered ‘āina momona (fattened land).

Kalo was baked or steamed and then often pounded into ‘ai pa‘a (firm food) or poi. Poi was eaten with the fingers and was often described as one-finger or two-finger poi depending on the thickness. Cultural understandings displayed in the protocol surrounding the eating of poi are mentioned by Mary Kawena Pukui in Native Planters,“My own people, among whom I grew up, never used three fingers…there was an etiquette involved: I was taught as a small child never to separate the fingers…never to insert the fingers above the first joint.”** These things were all considered piggish, greedy.

The kalo was pounded into pa‘i ‘ai (pounded food) and poi on papa ku‘i ‘ai (kalo pounding boards) with pōhaku ku‘i ‘ai (food pounding stones). These pōhaku were most often carved from basalt stones and formed with a rounded base and knobbed head. One derivation often found on the island of Kaua’i is a stirrup, handle shape. Bishop Museum’s ethnology collection contains hundreds of pōhaku ku‘i ‘ai in a number of styles, sizes and materials.

* Pukui, Mary Kawena. ‘Olelo No‘eau: Hawaiian Proverbs & Poetical Sayings. Bernice P. Bishop Museum special publication 71. no.1700, p.182. Honolulu. Bishop Museum Press, 1983.

**Handy, E.S. Craighill and Elizabeth Green Handy with the collaboration of Mary Kawena Pukui. Native Planters in Old Hawaii: their Life, Lore, and Environment. Bernice P. Bishop Museum bulletin 233. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1991. pp 115.

Location: Bishop Museum

Audio

“He Mau Inoa Kalo” performed by Kuluwaimaka

Recorded in 1933

Collection: Kuluwaimaka Collection

Call Number: Haw 2.13 (14)

Location: Bishop Museum Archives