Palaoa

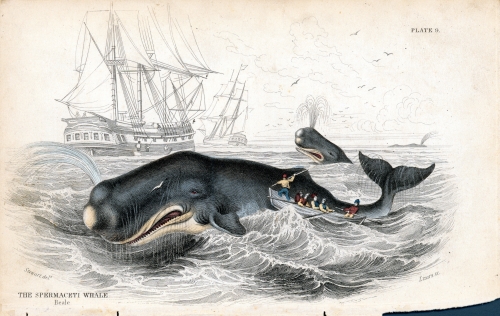

Sperm Whale

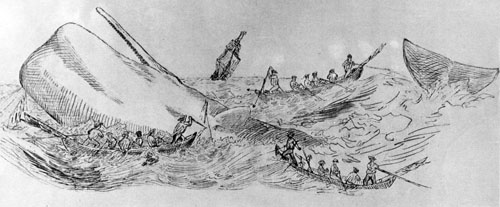

Whaling was an integral part of the development of many countries in the early nineteenth century. Whale blubber produced oil that lit the lamps and greased the machines of many of the most “modern” inventions of the time. It was said that whale oil was the illumination and lubrication of the Industrial Revolution. As the traditional hunting grounds of the Atlantic began to be fished out, whalers turned to the plentiful waters of the Pacific. Some of the most bountiful harvesting grounds were found off the coast of Japan. Japan’s ports however, were closed to foreign vessels, and with these whaling fleets needing a place to dock in order to replenish supplies, repair the ships and rest the crews, Hawai‘i became a perfect destination.

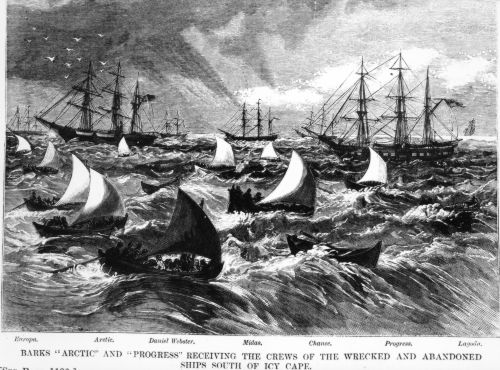

Whalers began arriving in Hawai‘i in 1819, and by 1822 over sixty ships were docking annually. This was the same period in which the Calvinist missionaries arrived in Hawai‘i and the two groups had vastly differing ideas about how these port towns should be run. The troubles at first were relatively minor but with the missionaries gaining more influence with the ali‘i nui, and laws against the sale of liquor and the taking of women being enforced, serious battles ensued. Lāhainā and Honolulu both saw several whaler uprisings and the Baldwin family home in Lāhainā was even the target of cannon fire from an angry ship captain.

By 1846, the number of whaling ships arriving in Hawai‘i had reached an astounding 596 and what had begun as a nuisance was now a major problem that was bringing much conflict to Hawai‘i. Sailors were the most prolific carriers of the diseases that seemed to spread through the Hawaiian population like wildfire, but the sailors also were carriers of another powerful force that would work to significantly redistribute resources in the islands. With the massive influx of people, and their money, a commercial market was born. The sailors, and their ships needed supplies, food, tools, liquor and many more commodities that often newly arrived “businessmen” were ready to supply. Hawai‘i became a “gold rush” town that attracted people of all types. Some of the most influential businesses in modern Hawaiian history got their start from the capitalist opportunities of this period. Hawai‘i also saw the loss of young Hawaiian men who traveled aboard these ships to the northwest coast of America and other destinations, never to return.

Prior to the arrival of whaling crews, Kānaka Maoli had a much different relationship to the whale. Whale ivory that washed ashore was considered sacred. One of the most powerful symbols of status was the whale tooth lei or lei niho palaoa. The beaches of Kualoa on O‘ahu were a major collection point for whale ivory and as such this ‘āina was considered the spot to control in order to possess all of O‘ahu.

The whale at Bishop Museum, unlike those that were caught for their oil, is actually a sperm whale. It was the first specimen installed in Hawaiian Hall in December of 1901 and has hung there ever since. It is over 55 feet long and weighs over two tons.

Location: Bishop Museum; Hawaiian Hall