The Pāʻū of Kamāmalu

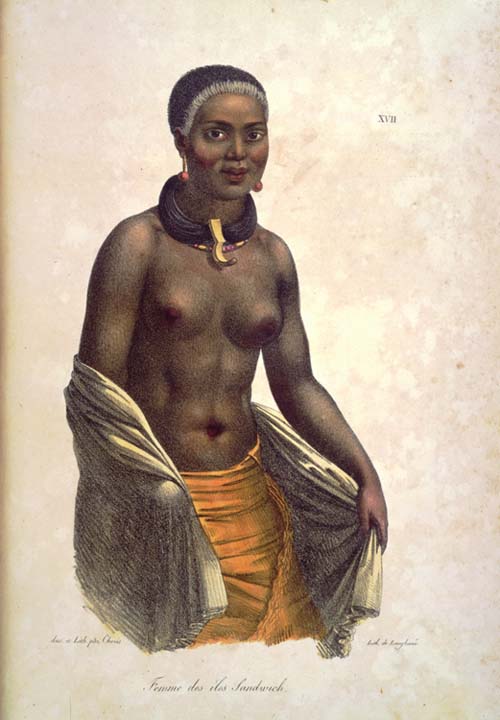

Prior to sustained contact with foreigners, the primary items of dress for Kānaka Maoli were the malo and the pā‘ū. The material used in the construction of both the malo of the kāne and the pā‘ū of the wahine was known as kapa. This finely pounded bark-cloth could be rendered to an amazing softness, yet still remain a durable and practical article of clothing or bedding. Various plants were utilized in the creation of this essential material; the most common being wauke (Broussonetia papyrifera) or paper mulberry.

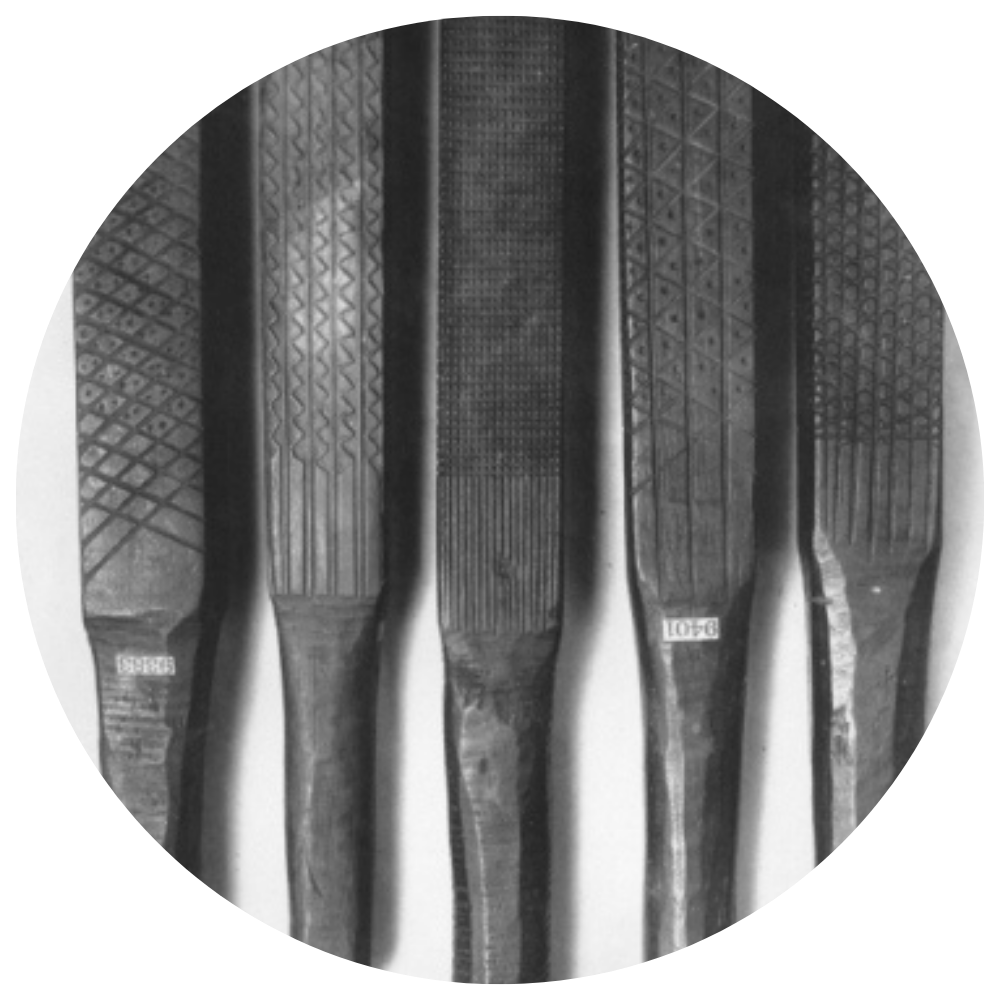

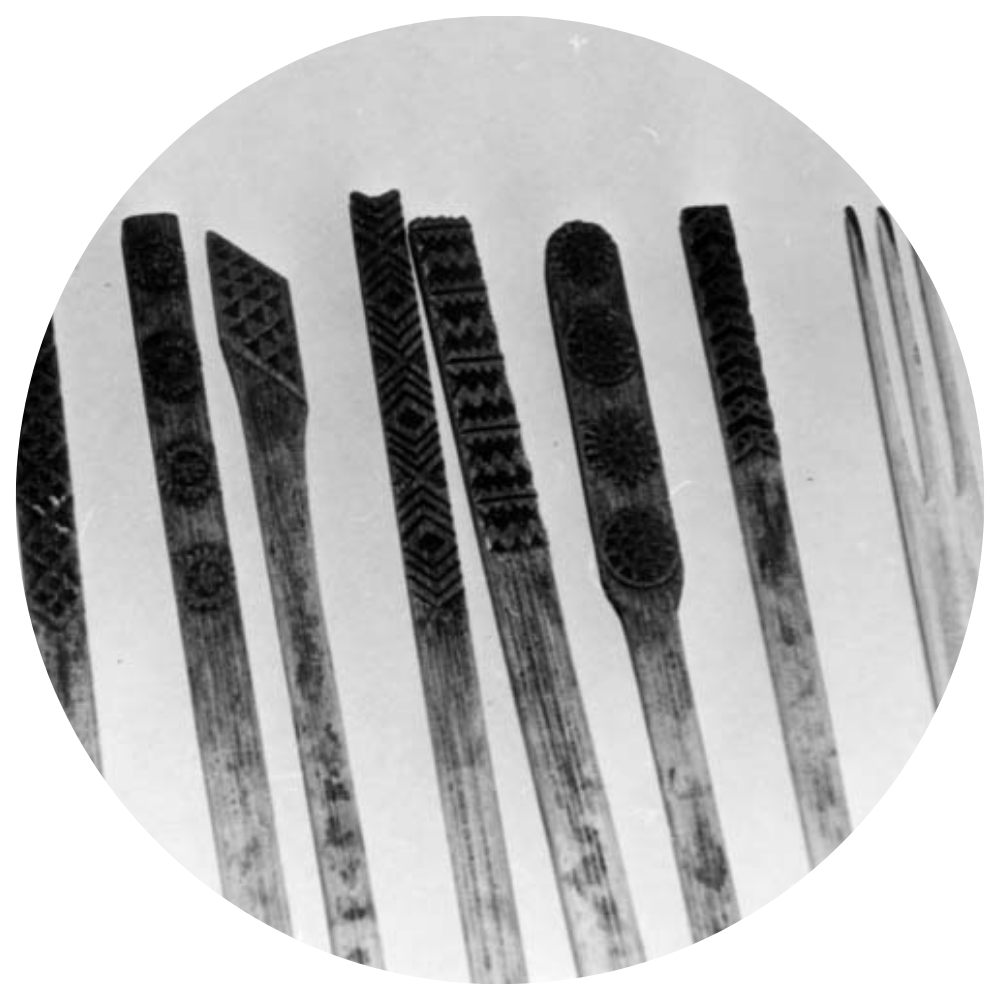

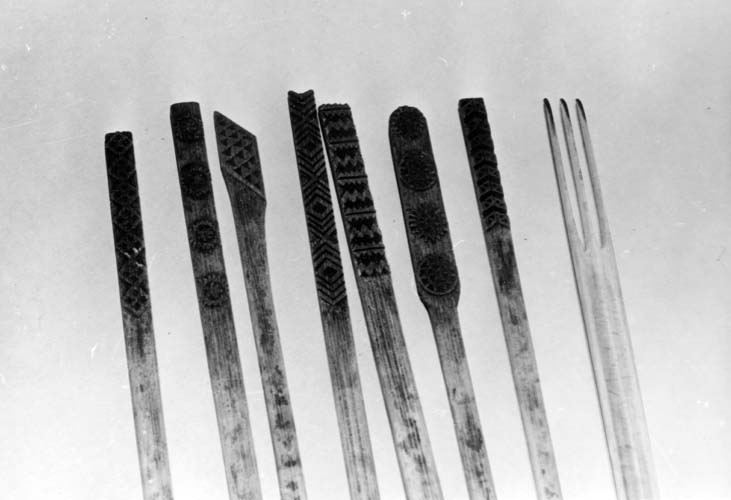

Kapa, like everything else in the Hawaiian world, was animate and held mana for its creator and wearer. Pieces were often painstakingly crafted and treasured as important possessions within an ‘ohana. Not only was the kapa itself a central part of traditional life, but also the work in creating the material brought Kānaka Maoli women together. Groups often gathered to beat the kapa and many traditional Hawaiian mo‘olelo refer to the echoing sound of the wooden kapa beaters resounding throughout the valleys of the islands.

The first wave of Protestant missionaries in 1820 viewed these scant coverings of Kānaka Maoli as immodest and lewd. Rev. Hiram Bingham, on first sighting Native Hawaiians, described the people as “chattering and almost naked savages.” The very strict mores of these New England Congregationalists clashed dramatically with traditional Hawaiian beliefs. Rising influence of the church meant great change in dress among Native Hawaiians as traditional pā‘ū were altered and later replaced with ankle to neck Mother Hubbards and mu‘umu‘u.

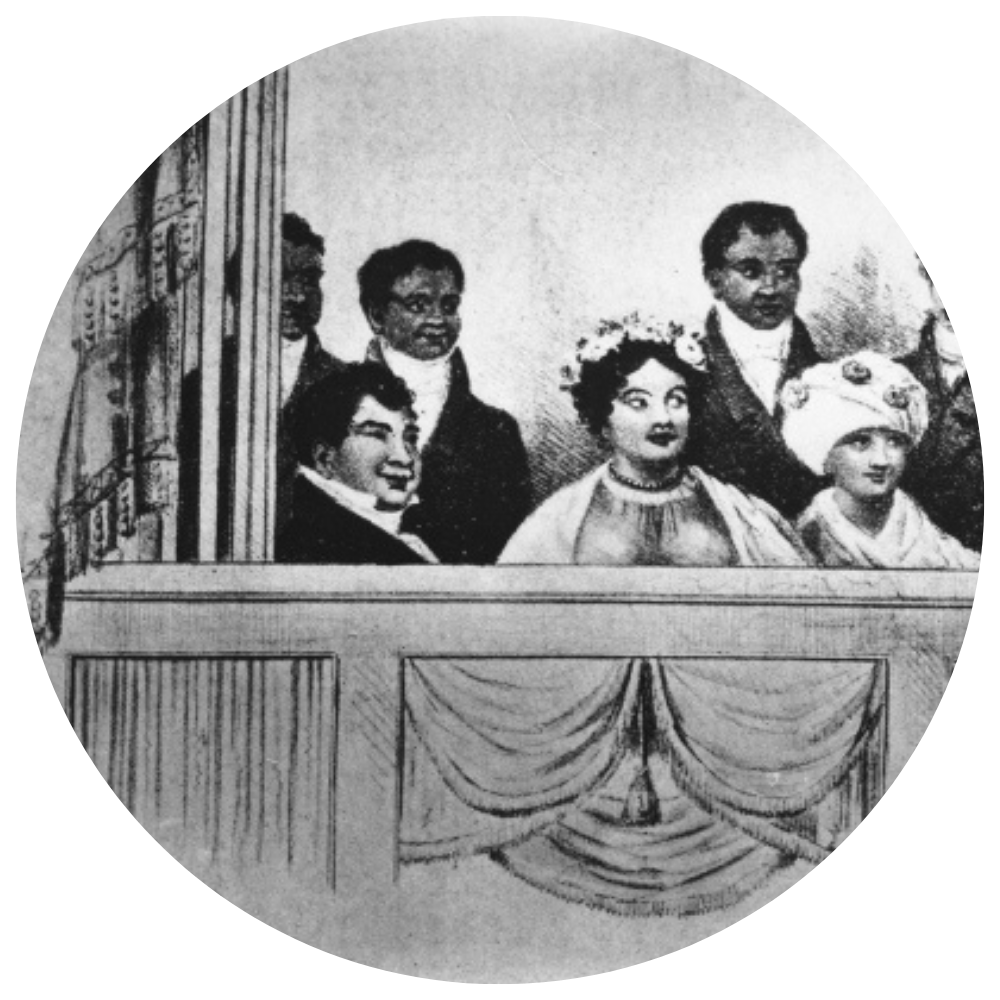

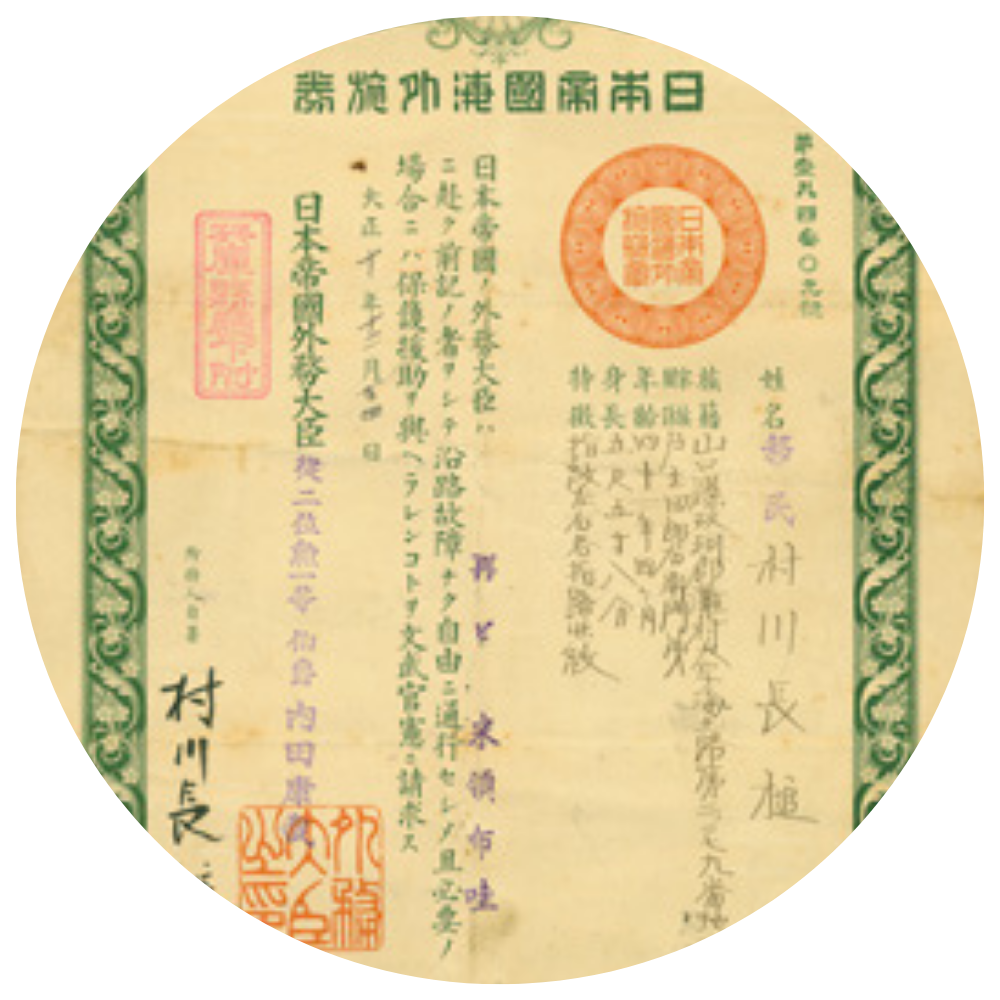

During this transition period the kapa itself changed as innovations brought by western technologies affected everything from applied colors to stamping techniques. The pā‘ū of Kamāmalu, Queen Consort to Liholiho, Kamehameha II, was one of these transitional pieces that incorporated new techniques in style and pattern. The Queen brought this pā‘ū with her on the Royal couple’s journey to visit King George IV of England in 1823-24. Both Kamāmalu and her husband Liholiho contracted measles in London and died. Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum received this pā‘ū from the family of Captain Valentine Starbuck of the ship L’Agile, the vessel that carried the King and Queen across the Atlantic.

Location: Bishop Museum