World War II Newspaper Headlines

December 7-8, 1941

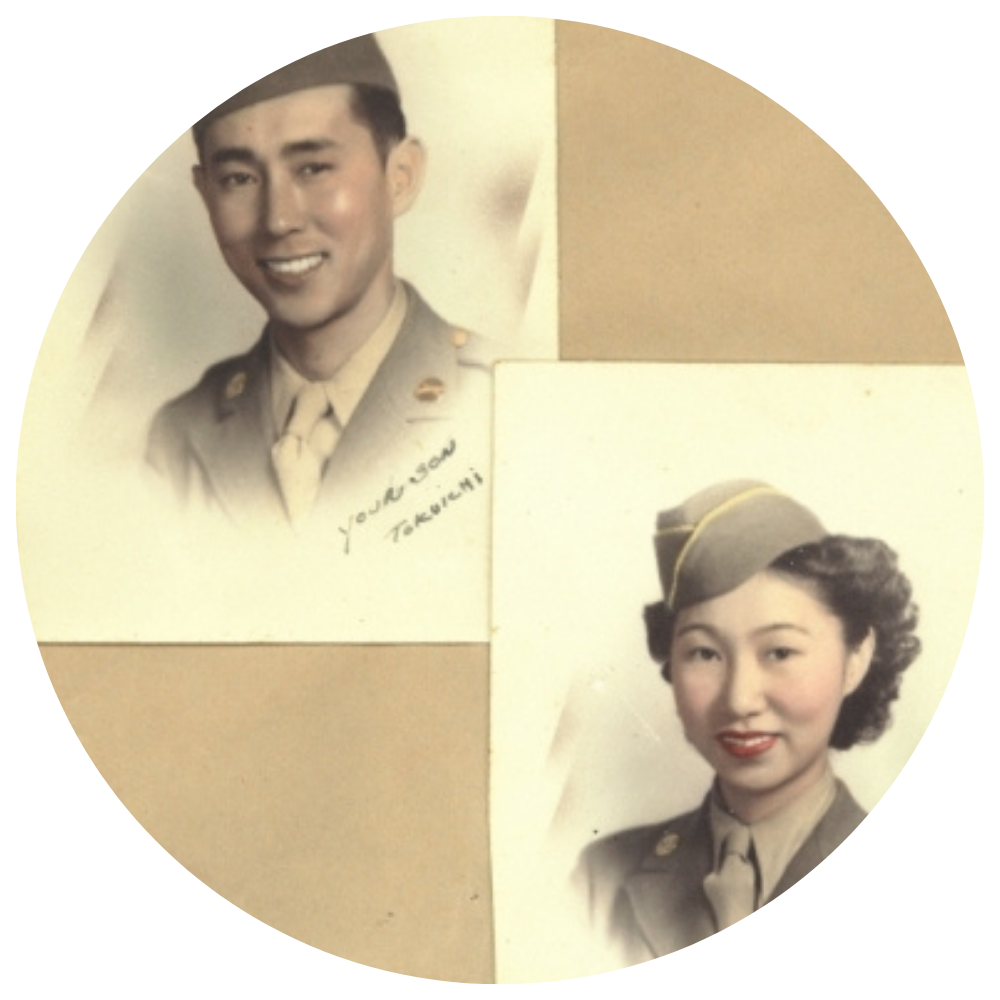

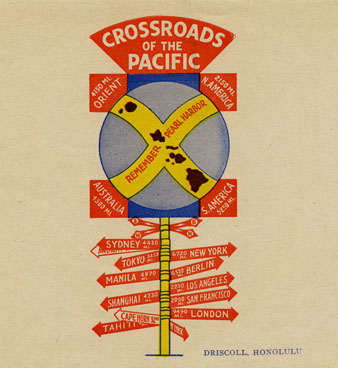

For many, the mention of Pearl Harbor brings images of Dec. 7, 1941. The impact of the Japanese attack on the United States Naval fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor not only defined a war, but for many came to define a place. For many Americans this place came to be a revered burial ground for war dead that had sacrificed their lives for their country. For many Kānaka Maoli it had already long represented something very different.

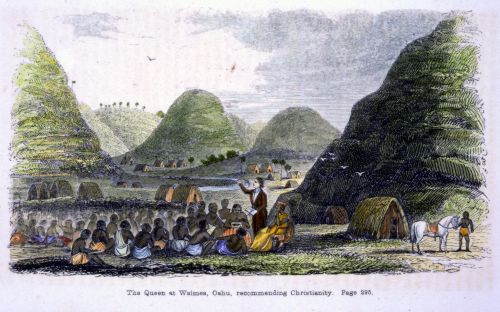

The area now known as Pearl Harbor was before called Pearl River Lagoon. This wahi pana (sacred place) was valued as an ‘Āina momona (fattened land), rich in natural resources that Hawaiians skillfully managed as large fishponds and taro lo‘i. This land fed entire communities. The land also was the home to revered ‘aumākua (ancestor gods) such as the shark goddess Ka‘ahupahau and others. It was in the 1870’s however that this region would come to represent something significantly new to many Kānaka Maoli.

The 1884 Supplementary Convention to the 1875 Treaty of Reciprocity between the Kingdom of Hawai‘i and the United States of America provided representatives of the two parties with entitlements that they very much desired. Those who had invested money in the growing of sugar in the islands were allowed to export their product to the United States markets free of importation tariffs, and the United States military gained exclusive lease rights to the long coveted deep-water port at Pearl River Basin. Sugar profits were to increase exponentially and the barons that ran these plantations were well pleased. King Kalākaua, who enjoyed the backing of these influential businessmen in his heated election victory over Queen Emma Rooke, had supported the treaty, but many Kānaka Maoli vociferously attacked the deal. Kānaka representatives such as Iosepa Kaho‘oluhi Nāwahīokalaniopu‘u and George W. Pilipo decried allowing the U.S. to establish a base at Pearl River Basin. They prophetically warned that this consent would be the beginning of the loss of Hawaiian sovereignty. To these Kānaka and others, Pearl Harbor came to represent the loss of their nation.

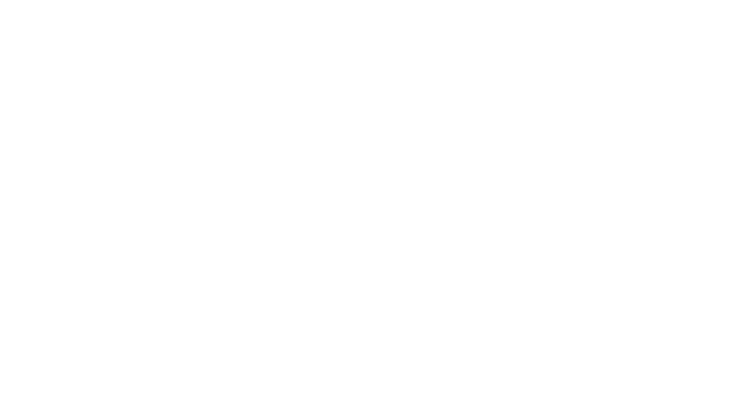

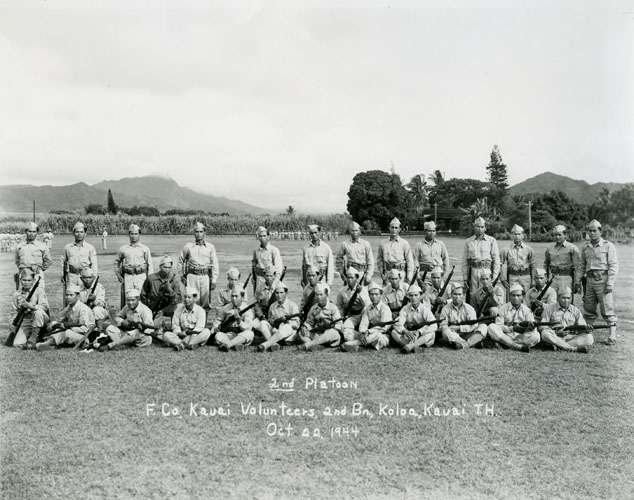

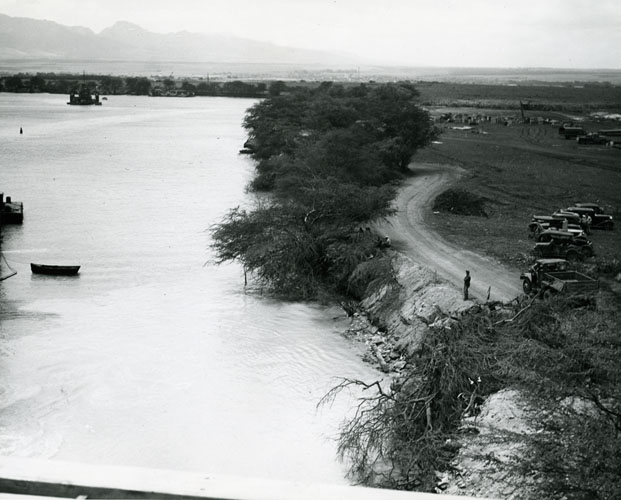

The effects of the Dec. 7, 1941 bombing were far reaching and changed the lives of all those who lived here in the islands. People in locations around the islands, not just Pearl Harbor, died in the attack. Later the same day, martial law was declared, the writ of habeas corpus was suspended and army troops began to take up positions around all of the major islands. Army General Walter Short took over power of the government as Military Governor. Curfews, censorship of newspapers and mail, and rationing became the new order. Japanese, long a major portion of the population in the islands, became the questioned enemy and Japanese businesses were closed down. Government buildings in Hawai‘i, including ‘Iolani Palace were turned into military bases. Over the following years of the war, lands deemed necessary for military training, transport and other uses were condemned and appropriated by the military. Private property such as that at Waipi‘o, Hawai‘i that was converted into an amphibious assault base and the entire island of Kaho‘olawe became military-owned lands. While martial law was initially proposed as a temporary measure, it was to remain in effect for nearly three years.

Location: Bishop Museum Library

Collection: Newspaper Collection